|

|

The Interplay Between

Classical Music, Ragtime, and Jazz (featuring the Desecration:

Rag Humoresque by Felix Arndt) By Ted Tjaden

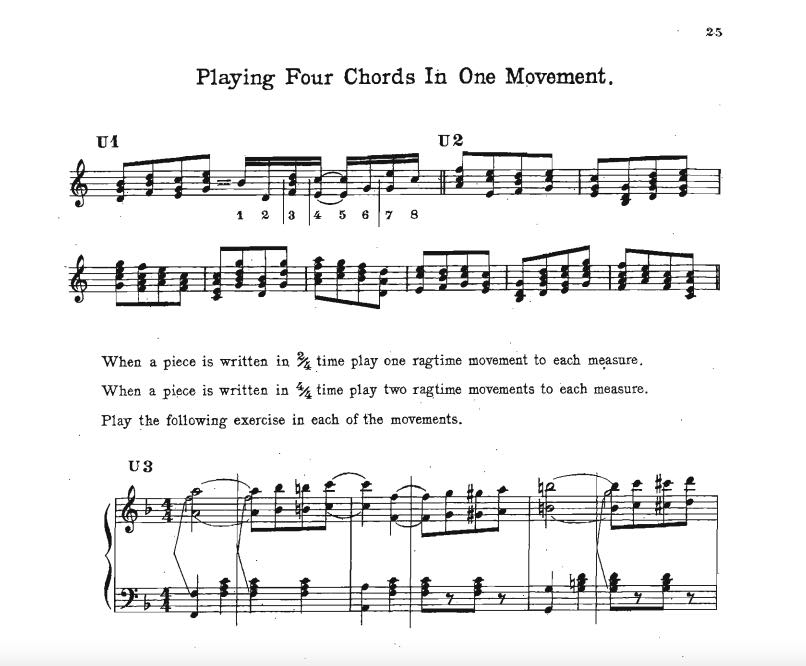

This essay discusses classical music in ragtime and jazz and the influence of ragtime and jazz on classical music composers. The technique of "ragging the classics" involves the composer or performer using the melody from a piece well-known classical music and syncopating the tune with ragtime syncopation. Just as as ragtime composers would syncopate the melodies of classic music compositions, classical music composers were also influenced by the melodies and rhythms of ragtime music. Although I usually view classic ragtime piano narrowly, as covering a roughly 20-year period from 1899 to 1919, this essay also touches up "jazzing the classics" and jazz motifs in classical music that followed the ragtime era through to to ragtime revival era to present. As a result, this essay includes a fairly broad array of composers and performers beyond the usual suspects. In Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History, in speaking of the advanced era of ragtime from 1913 to 1917, the authors note that "[o]ne of the oldest show business devices is to take a classical composition and syncopate it" and the "[t]he ragging of the classics suddenly blossomed forth in this era with great skill and cleverness" (Jasen & Tichenor: 172). Berlin notes in similar terms that "'[r]agging the classics' was an especially popular exercise" and documents the following description of Ben Harney "ragging the classics" in 1899: His performances including the "ragging" of such popular classic's as Mendelssohn's Spring Song, Rubenstein's Melody in F, and the Intermezzo from Mascagni's "Cavalleria Rusticana," which he would first play in their orthodox form. The effect was startling [Berlin: 67].Likewise, author John Edward Hasse in "Ragtime: From the Top" in Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music, notes that the "ragging" of the classics predates the publication of ragtime sheet music and that many of these performances were never transcribed: [Another] type of ragtime was "ragging" of classics or other preexisting music. Mendelssohn's "Spring Song" and "Wedding March" and Rubenstein's "Melody in F" were among the favorite classics for "ragging." To "rag" is to syncopate the melody of nonsyncopated work. This technique, which predates the first publication of rags by several decades, was a common performance practice of pianists. Most of this type of ragtime, like most modern jazz improvisations on existing popular songs, was probably never written down or recorded (Hasse: 6).Another view regarding ragtime and classic music is that some "classic" ragtime piano approaches being "classical music" in its own right. Gunther Schuller, for example, in "Rags, the Classics, and Jazz" in Hasse, Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music, argues that some of the more sophisticated instrumental rags, such as Lamb's Ragtime Nightingale, could be considered as having the same complexity and expressiveness as some classical music compositions: Classical yearnings in ragtime may take another form of expression: in the overall mood or stance of a piece, as in the many rags of Joseph Lamb (1887-1960). Take his moving, poignant Ragtime Nightingale (1915), an extensive "mood poem," albeit within the standard duration and multithematic form of the piano rag. Unhurried, contemplative, at once simple and grand, haunting, and at times vigorously swinging, Ragtime Nightingale embodies the full spectrum of ragtime's expressions. From the almost Tchaikovskian moodiness of the opening C-minor section with its graceful descending sixths in the middle measures, through the more energetic E-flat second theme to the scintillating Trio in A flat, the piece is a pure joy to hear [Hasse: 86].A 1925 article from Melody magazine also argues that American ragtime and jazz music was its own form of American classical music: Our highbrows for years have talked much of the need of declaring our independence of old world forms and inspirations. Well here we have it, in musical forms which are as intensely and significantly American as Verdi's are Italian, or Schumann and Wagner, German. It is as racy as our soil as an Irish folk song is of Ireland. It is the rush of our racing streets. It has all the bright contrasts of our racial conglomerate. It has our moods and our spirit, our impudence and irreverence, our joy in speed and force. American musical genius has in ragtime and jazz contributed something of great vitality to the art of music, in its rhythms and new colorings. [Rackett: 3]In fact, John Stark, the main publisher of Scott Joplin, James Scott, and Joseph Lamb, was known for his hyperbolic marketing of the "classic" ragtime sheet music published by his company, and in the following statement puts Stark-published rags on par with the "genius" and "psychic advance thought" of compositions by Chopin and Bach: Since we forced the conviction on this country that what is called a rag may possibly contain more genius and psychic advance thought than a Chopin nocturne or Bach fugue, writers of diluted and attenuated imitations have sprung up from Maine's frozen hills to the boiling bogs of Louisiana (Blesh: 118).Classical musical composer Darius Milhaud (discussed below) also argued at the time that the elements of tone and rhythm in the orchestrated jazz music played by Paul Whiteman's orchestra (including compositions by Gershwin) were a form of (American) classical music that puts to shame the need to "rag the classics": They have brought us absolutely new elements of tone and rhythm of which they are perfect masters. But these jazz bands have hitherto been used only for dancing, and the music written for them has not got beyond ragtime, the foxtrot, and the shimmy. It was a mistake to adapt pieces of music already famous — ranging from Tosca's prayer to 'Peer Gynt' or Grechaninov's Berceuse — making use of their melodic elements as dance themes. This is an error of taste, as bad in its way as the employment of motor-sirens with percussion instruments. [Milhaud: 171]However, musician Frederick Hodges in his essay "Is Ragtime 'Classical Music'?" points out the differences between ragtime and classical music, arguing that ragtime as "popular" music arose due to different purposes and motivations (including the sale of sheet music) whereas composers of classical music had different motivations: Ragtime is not classical music. Ragtime is popular music. Classical music and popular music serve entirely different purposes and have diametrically opposed motivations behind their creation. In general, a classical composer uses music to express his deepest emotions and experiences. Classical music arouses the intellect and the passions. It addresses the deepest questions of human existence. Classical music is sophisticated and intelligent. The impression is that it cannot be appreciated by the uninititated and the uneducated. Of course, classical composers were traditionally supported and constrained by the patronage system. Poverty may have obliged Mozart to accept commissions for works he might not otherwise of written, but his patrons probably never asked him to "dumb it down." The point of sale was a single event — the check from the patron rather than multiple points from a sheet-music buying public.Hodges does acknowledge the intrinsic qualities of certain ragtime compositions (and I don't think he would necessarily disagree with Schuller's appreciation of Lamb's Ragtime Nightingale) and that the relation between ragtime and classical music may be quite fluid: While it would be a grave mistake to equate the rags of Scott Joplin or the popular songs of Cole Porter or George Gershwin with classical music, the musical output of these and many other popular composers was nevertheless of such excellent quality that it may (and should) endure for centuries as the pinnacle of American musical achievement in the twentieth century. Indeed, as Rifkin's recordings and as Gershwin's successful forays into classical music proved, the border between popular and classical music could be quite fluid. In fact, many composers of popular music, such as Gershwin and Ferde Grofé, easily transitioned back and forth between between popular and classical music. Nevertheless, Joplin and Gershwin are among the exceptions. Few would argue that the George Botsford's "Black and White Rag" belongs in the same category as Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring."This essay addresses the relationship between ragtime, jazz and classical music by first looking at compositions from the ragtime and jazz era that use classical motifs and by then looking at classical music composers who were influenced by ragtime and jazz. As such, section 2 below sets out sheet music, when available, for ragtime era compositions where composers — including those by Felix Arndt, Irving Berlin, Alex Christensen, Edward Claypoole, George Cobb, Artie Matthews, and Paul Pratt – employed classical motifs or ragged the compositions of classical music composers. Section 3 below instead discusses ragtime era composers who "classicized" ragtime with their more sophisticated ragtime compositions. Section 4 below then moves to the jazz and modern era by discussing and modern era composers and performers who "ragged" and "jazzed" the classics, such as George Gershwin and Alec Templeton. Section 5 below then discusses ragtime and jazz motifs in classical music, including compositions by Claude Debussy and Erik Satie. Section 6 below sets out links to commercial and online recordings of "ragging" and "jazzing" the classics followed in section 7 below with a bibliography of resources. 2) Ragtime era composers who "ragged" the classics [toc] [top] There were a number of ragtime era composers who published compositions on classical music themes or who were influenced by classical music, the most well known of which in this genre include Felix Arndt, Irving Berlin, Alex Christensen, Edward Claypoole, George Cobb, Artie Matthews, and Paul Pratt. The sheet music to compositions by these and other ragtime era composers is set out below by composer, as follows:

a) Harry Alford [toc] [top] Harry Alford was known for his prowess as a music arranger, as noted by Rick Benjamin in a 1993 article in the following terms: Harry Alford elevated the arranger's role from that of a drudging technician to that of a creative artist; his ingenious and quirky arrangements soon made a sensation. Within a few years, just about everyone in the entertainment business wanted their music scored by him. Business boomed, and between 1904 and 1924, his studio turned out over 34,000 separate arrangements!Benjamin notes that some of Alford's most famous arrangements include "Some of These Days" (1910), "Melancholy Baby" (1912), "Let Me Call You Sweetheart" (1910), "I Ain't Got Nobody" (1916), "The Darktown Strutter's Ball" (1916), "It Had to be You" (1924) and "Down by the Old Mill Stream" (1910). The following of his compositions are available online: “Glad Days: Novelette” (1920) and “Soul of the Violet: Romance” (1922). In the following piece, Alford has given orchestral ragtime treatment to "Chi me Frena in Tal Momento" from Gaetano Donizetti's opera Lucia de Lammermoor:

b) Felix Arndt [toc] [top] Felix Arndt (20 May 1889 – 15 October 1918) was an American composer and prolific maker of piano rolls. Two of his more famous rag/novelty compositions are Nola: A Silhouette for Piano (1914) and Marionette (1914) (for a 1917 Victor recording of Felix Arndt playing Marionette, click here). Arndt's most famous example of syncopating classical music is his Desecration Rag from 1914 setting out ragtime versions of the following classical compositions:

Two years later, Arndt published the following piece with An Operatic Nightmare: Desecration Rag (No. 2), his ragtime take on the following operas:

c) Irving Berlin [toc] [top] As noted in his Wikipedia entry, Irving Berlin wrote over 1,500 songs, including the scores for 20 original Broadway shows and 15 original Hollywood films, with his songs nominated eight times for Academy Awards. Known for many popular songs – including Alexander's Ragtime Band, Easter Parade, Puttin' on the Ritz, Cheek to Cheek, White Christmas, Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better), and There's No Business Like Show Business – Berlin wrote the following ragtime song in 1909 doing a take on Felix Mendelssohn's Spring Song:

In 1910, Irving Berlin published the following song, made famous by May Irwin:

In Opera Burlesque (1912), the song opens up with the following lyrics: Let's sing some Ragtime Op'ra,

Irving Berlin's debut musical, Watch Your Step (book by Harry B. Smith) (1914), which features his Syncopated Walk (1914) [listen to 1915 recording], the composer also rags opera tunes in the Act II Finale in "Opera in Modern Time" in which, as noted in the Wikipedia article for this musical, melodies from famous operas were turned into popular dances of the time, with the ghost of Verdi appearing to protest the ragging of his Rigoletto, to no avail (the operas parodied include Verdi's Rigoletto and Aida, Gounod’s Faust, Bizet’s Carmen, Puccini’s La Bohème, and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci) (note: the sheet music below has the title Ragtime Opera Medley):

For a large online collection of Irving Berlin sheet music, see the online holdings of Irving Berlin songs from the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection. For more resources on Irving Berlin, see:

d) Alex Christensen [toc] [top] My separate essay on Alex Christensen documents the role that Christensen played in the spread of the popularity of ragtime through his instruction manuals, publication of the Ragtime Review, and publisher of his own compositions and those of others.

The first example below by Christensen of "ragging the classics" is his ragtime version of Mendelssohn's Wedding March:

Another example is Christensen ragging Gustav Lange's Flower Song (Blumenlied):

In the following piece, Christensen does his ragtime versions of the following classical compositions: Franz Liszt's Liebestraum, Anton Rubinstein's Melody in F, and “My Heart at Thy Sweet Voice” from Camille Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah:

In addition, Robert Marine, a teacher within the Christensen school system, also may have ragged the classics in the following hard-to-source piece of sheet music based on the words "keyboard" and "klassic" in the title:

e) Edward Claypoole [toc] [top] Edward Claypoole (20 December 1883 – 16 February 1952) was a child prodigy at piano and sold his first two compositions, Prancin Jimmy (1899) and Cake-walk Lindy (1900), in 1900 to Joseph Stern: Jasen and Tichenor (1978): 170. He is also known for his Reuben Fox Trot (1914) and American Jubilee (1916). Despite working most of his life as a court clerk, Claypoole is credited with over 500 compositions, including a number of novelty rags, such as Jazzapation (1920), Skidding – Novelty Solo (1923), Dusting the Keys (A Dusty Rag Fox Trot) (1923), and Bouncing on the Keys (1924): Jasen and Tichenor (1978): 172-73. In Ragging the Scale (below), Claypoole does a clever riff on traditional piano scale exercises, selling over 2 million copies (for a modern homage to this piece, see Bill Edward's Hanon Rag, discussed below). However, according to Jasen and Tichenor, Claypoole saw no royalties for Ragging the Scale since Claypoole sold the piece outright to the publisher for $25 (Jasen and Tichenor (1978): 172-73. For Claypoole to have been denied royalties is perhaps appropriate because, according to Al Rose's humorous re-telling of Eubie Blake's account of this piece in Eubie Blake [Rose: 40-41], Eubie Blake had in fact perfected ragging the scale in five keys in playful competitions with Hughie Wolford in 1905 or 1906 in Baltimore, well prior to Claypoole publishing "his" version in 1915.

f) George Cobb [toc] [top] In my separate essay on George Cobb I set out links to all of his 215 known ragtime-related compositions, including some of his more famous pieces, such as Rubber Plant Rag: A Stretcherette (1909), Aggravation Rag (1910), Rabbit's Foot (1915), The Midnight Trot (1916), Cracked Ice Rag (1918), Irish Confetti: Fox Trot (1918), Feeding the Kitty: A Ragtime One-Step (1919), and Piano Salad (1923). Known as a clever and prolific tune-smith, Cobb also dabbled in "ragging the classics." In the first example, Cobb rags the main melodies from "In the Hall of the Mountain King" from Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt, Suite No. 1, Op. 46:

The next example, the Russian Rag, was likely one of Cobb's most famous of all of his many compositions, being his ragtime version of Rachmaninoff's Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op.3, No.2, a piece that was so popular that he did a "new" version of the rag in 1923, listed below.

Cobb returned to Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt, Suite No. 1, Op. 46 by ragging the second song in that suite, "Aase's Death" in the following piece:

Cobb also arranged a ragtime version of the "Anvil Chorus" from Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore with the Blacksmith Rag by Rednip (an alias for Harold Pinder) with words by Will Garton and Leo Wood:

In the following piece, as noted by Hodges, Cobb syncopated several themes from the music of Anto nín Dvořák:

In the following piece, as also noted by Hodges, Cobb syncopated several themes from the music of Franz Schubert’s "Ave Maria" and themes by Moritz Moszkowski:

In Torrid Dora (Toreador), a piece listed in That American Rag [ Jasen and Jones (2000):374], Cobb does his ragtime take on the "Toreador's Song" from Carmen by Georges Bizet:

After the success of the Russian Rag (1918) (above), Cobb released the following variations on the same them with The New Russian Rag, also listed in That American Rag [Jasen and Jones, 2000: 376]:

Finally, in the following piece, Cobb published a syncopated version of Cécile Chaminade's Scarf Dance, op. 37:

g) Carleton Colby [toc] [top] Carleton Colby (1881-1937) was a cellist, organist, arranger, and manager of the Harry L. Alford music studios in Chicago, as noted in an online obituary. He died suddenly on July 23, 1937. Compositions written or arranged by Colby span a 40-year-plus period and include the following titles (and I assume this list is incomplete): I Can't Take My Eyes Off the Pitcher! (1910) (by A.V. Hedin) (words by Carlton Colby); The Maid in the Moon (from “The Cat and the Fiddle”) (1912); Pick a Chicken: One-Step and Trot (by Mel B. Kaufman) (arranged by Harry Alford and Carleton Colby) (1914); Tattered Opera (1914); Good Bye Rag (1920) [in Ragtime Jubilee folio, Dover]; Faith: A Sacred Solo (1928); Lee Sims Piano Method (Jazz) (editor) (1928); Headlines: A Modern Rhapsody (1934); Going Down to London (1935); Cowboy and Mountain Songs: Orchestra Folio No. 1 (1936); Three Blind Mice: Scherzo (1936); Softly Steals the Night (A Spanish Serenade) (by Egbert van Alstyne, arranged by Carleton Colby) (1934); The Toy Shop: Descriptive Fantasy for Narrator and Concert Band (1956). In the following piece, Colby composed a ragtime version of Giuseppe Verdi's 'Miserere d'un alma gia vicina" from Il Trovatore:

h) Zez Confrey [toc] [top] Edward Elzear "Zez" Confrey (3 April 1895 – 22 November 1971) composed a number of "novelty" piano compositions, the most famous of which include Stumbling (1912), My Pet (1921), Kittens on the Keys (1921), Coaxing the Piano (1922), Nickel in the Slot (1923) and Dizzy Fingers (1923). Confrey also composed a number of pieces that ragged the classics or that contained classical music motifs, including the following compositions (author's note: I prepared this entry on Zez Confrey quickly in January 2022 and have not had time to research the following pieces in detail, some of which I have included based solely on their title; in addition, this list may not be complete – I would hope to expand this section on Confrey sometime in the future):

i) George Fairman [toc] [top] George Fairman (1881-1962) was a composer of ragtime and patriotic songs, including but not limited to The Bugavue Rag (1902), Way Down South (1912) (listen to 1913 recording), I'm the Guy Who Paid the Rent for Mrs. Rip Van Winkle (1914), Sailor Boy (words by Edward Ridge) (1914), I Think We've Got Another Washington and Wilson is His Name (1915), Hello America, Hello! (1917) (listen to 1918 recording), I Don't Know Where I'm Going But I'm On My Way (1917) (listen to 1917 recording), When You Find There's Someone Missing (1917), He's A Better Man Than You, Kaiser Bill (1918), I'd Love to Dance an Old Fashioned Waltz (1918), Here's to Your Boy and My Boy (1918), Bo-La-Bo: Eqyptian Fox-Trot Song (1919) (listen to 1920 recording), Not in a Thousand Years (1919), Everybody Tells It to Sweeney (words by Sydney Mitchell) (1920), If Shamrocks Grew Along the Swanee Shore (1921), She's Always Singing the Blues (words by Al Bernard) (1921), and Kiss Mama, Kiss Papa (lyrics by Al Herman) (1922). According to Jasen and Jones (2000: 321), George Fairman composed under the pseudonym Joe Arizonia. Fairman is included here for the following compositions that "rag" the classics, with the later ones done more in a novelty piano style:

j) Bert Grant [toc] [top] Bert F. Grant (12 July 1878 – 10 May 1951) was a prolific composer of ragtime songs, including The Rose and the Honey Bee (lyrics by Malvin Franklin) (1909), I'm the Guy (words by Rube Goldberg) (1912), and Broadway: Don't Blame it All on Broadway (1913). There are a large number of his ragtime songs available online here, here, and here. He is also the composer of Aero Rag (1910). He is included here for the following novelty piano piece that includes the ragging of Rachmaninoff's Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op.3, No.2:

k) Arthur Gutman [toc] [top] I could not find much information about Arthur Gutman who was the composer of Carmencia (Castillian One Step) (1919) [listen to MIDI file], the music arranger for 9 Broadway shows spanning 1916 to 1936, and editor of The Prairie Ramblers and Patsy Montana's Collection of Songs (1936). He is included here for the following composition, listed in That American Rag [Jason and Jones (2000): 398] since, I presume, it is a ragtime version of Franz Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody no. 2 for Piano (but I cannot verify that since I have not been able to source a copy of this composition):

l) E Clinton Keithley [toc] [top] E. Clinton Keithley (1880-1955) was a ragtime composer known for the following two rags, both listed in That American Rag: Dixie Kisses: Rag Intermezzo (1909) and Bumble Bee Rag (1909) [listen to piano roll]. He also composed a number of ragtime songs, available online here and here. In addition, there are a number of online piano roll recordings of his songs played by various performers. The following composition is Keithley's ragtime version of melodies from Franz Lehár's The Merry Widow:

m) Max Kortlander [toc] [top] Max Kortlander (1 September 1890 – 11 October 1961) was a prolific composer of novelty rags and songs as well as being famous for his hand-played piano rolls, as noted by Jasen (2000: 123-24): Kortlander was a composer of extraordinary rags, a brilliant piano-roll arranger of pop tunes of the day, and a magnificent performer of hand-played piano rolls, eventually going on to become president of QRS in 1931, which he owned until his death.Some of his instrumental compositions include the following pieces: Blue Clover Man (1920), Hunting the Ball Rag (1922) (unpublished), Deuces Wild (1923), Red Clover (1923), Shimmie Shoes (1923), Black'n Blue (1924), Buck Shots (1924), Butter Fingers (1924), Flowers of Spain (1924), On Hawaiian Sands (1924) , Left Hand Tricks (1924), New Orleans Fizz (1924), Rain Drops (1924), and Silver Screen (1924). For a good recording of Kortlander's piano rolls, see Piano Roll Artistry of Max Kortlander (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings) (1981). In the following piece, Kortlander does a ragtime version of Frederic Chopin's Funeral March:

n) Henry Lange [toc] [top] Henry Lange (20 July 1895 – 10 June 1985) was a pianist for Paul Whiteman’s orchestra in 1920 and performed during the evening of the debut of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in 1924. He composed novelty compositions with Jack Mills, including Whippin’ the Ivories (1922) [listen to performance] and Page Mr. Pianist (1922) [listen to MIDI file]. Lange is included here for the following novelty instrumentals that syncopate classical music themes:

o) Julius Lenzberg [toc] [top]

In Operatic Rag, Lenzberg does a ragtime version of a number of famous opera arias, including:

Although I have not yet identified a classical music antecedent for Rag-A-Minor by Lenzberg, I have included it here since it sounds as though it could have been influenced by classical music motifs:

p) Victor Maurice [toc] [top] There is little information available about the following composer and what appears to be a version of "ragging" Franz Lehár's The Merry Widow:

q) Will Morrison [toc] [top] Will Morrison (12 October 1874 – 18 December 1937) was a mid-West ragtime composer affiliated with the publisher J.H. Aufderheide. In That American Rag, Will Morrison is described as being "besotted" with ragtime, publishing Cecil Duane Crabb's Fluffy Ruffles in 1907, which was soon thereafter picked up by J.H. Aufderheide in 1908 (Jason and Jones (2000): 154). Will Morrison is known for for Trouble Rag (with Cecil Duane Crabbe) (1908), Dance of the Sun Rays: Valse Impromptu (1909), Scarecrow Rag (1911), Sour Grapes Rag (1912), Will o' The Wisp: Syncopated Waltzes (1912), and That Waltz (1914). In the following piece from 1915, Morrison does a ragtime waltz version of Antonín Dvořák's Humoresques:

In the following piece from 1915, Morrison does a ragtime waltz version of Anton Rubinstein's Melody in F:

In addition, from the same publisher (Warner Williams) is the publisher's arranged version of a syncopated waltz on the themes from Il Trovatore:

r) Paul Pratt [toc] [top] Paul Pratt (1 November 1890 – 7 July 1948) was a prolific mid-West composer of ragtime era compositions as well as a piano roll performer, perhaps being most famous for Vanity Rag (1905), Colonial Glide (1910), Hot House Rag (1914), and On the Rural Route (1917), along with the classically-themed Springtime Rag, based on Felix Mendelssohn's Spring Song:

s) Paul Rubens [toc] [top] Paul Rubens (29 April 1875 – 5 February 1917) was an English songwriter who is most well known for writing musical comedies for the English stage. Rubens also wrote a number of compositions of likely interest to most ragtime musicians, including:

t) Aubrey Stauffer [toc] [top] Aubrey Stauffer (born 14 June 1876) was a composer of ragtime era novelty songs. For someone who appears to have been a fairly prolific composer, there is very little information about Aubrey Stauffer online, including no "master list" of his compositions. The BMG (Banjo, Mandolin, Guitar) Journal (June 1927) at 133 describes Stauffer as "one of the best-known mandolists in America". From various searches, it appears that Stauffer wrote primarily novelty songs, with many of them for the musical theatre stage and many of them self-copyrighted by him (indicating Chicago as the city of publication). Here is the best list I could compile of his compositions: Huckleberry Finn: A Missouri Intermezzo (1904), My Marguerite (with Edward G. Hill) (1904) (as a mandolin duet), My Vision (with T.L. Le Fever) (1904), Ben Hur: Overture, op. 28 (1906) (listen to a 2011 performance), Consequences or What a Little Smoke Will Do (with Al G. Coney) (1907), Chicago (1909) (words by Jimmy O'Brien) (1909), I'm Lonesome for You All the Time (music by Ernie Erdman, words by Aubrey Stauffer), Oh! You "Jeffreies" (with Milton Weil and Roger Lewis) (1910), That Peculiar Rag (1910) (as publisher), Oh That Oriental Rag (with Ernie Erdman) (1911), My Sweet, Sweet Evenin' Star: A Classic Novelty Song (with Ernie Erdman) (1911), Let's Play Post-Office (with Ernie Erdman) (1911), The Wreck of the Titanic (1912), Oh, You September Morn (words by Arthur Gillespie) (1913), Oh Skin-nay! C'mon Over! (words by Ruth Owen Riggs) (1913), Beautiful Dreams I'm Dreaming (with Arthur Gillespie) (1913), I Can Get Enough of Everything but You (words by WM Baltzell (1917), The Young Rajah ( 1922) (listen to a 1922 recording), Hollywood Fox Trot (1923) (listen to a 1923 recording), When a Little Boy Loves a Little Girl (1924), and Carry on for General MacArthur: A Marching Song (1942). In the following song, Stauffer gives ragtime song treatment to Robert Schumman's "Traumerei" from Kinderszenen, Op. 15.

u) Harry Thomas [toc] [top] Harry Thomas was born Reginald Thomas Broughton in Bristol England but immigrated to Montreal, Canada, when he was 19 years old (Gilmore 1989: 280). Apparently, Thomas had no formal musical training and was self-taught but "studied" under Willie Eckstein and would play at the Strand Theatre in Eckstein's absence: The two men, though dissimilar in temperament and musical training, shared a fondness for two pleasures – liquor and improvisation. Both pianists could spontaneously weave snippets of melody from popular songs and classical masterpieces into an engaging and often humourous musical commentary on the events silently unfolding on the theatre screen (Gilmore 1988: 17).In the fall of 1916, Harry Thomas went to Chicago to record piano rolls for QRS Company and then on to New York to record Delirious Rag and Perpetual Rag for Metro-Art and Universal (Gilmore 1988: 17). Later that year, he returned to New York to record for Victor Talking Machine a 78 rpm with Delirious Rag on one side and A Classical Spasm on the other side, also manufactured in Montreal by the Berliner Gramophone Company (see above for his recording of A Classical Spasm). These recordings, according to Gilmore (1989:281) made Thomas the first musician resident in Canada to record ragtime. Harry Thomas is included here for the following recording even though no sheet music for the composition is known to exist:

v) Edward Winn [toc] [top] Edward Winn, who began his School of Popular Music in Newark, N.J., in 1901 (Jason and Jones, TAR: 124), was the author of various ragtime instruction manuals, including Winn's Practical Method of Popular Music: Rag and Jazz Piano Playing (circa 1920), listed in my separate essay on Alex Christensen and the ragtime instruction manuals of Christensen and others. In addition, from 1918 to 1919, Winn also authored a column in Melody magazine called 'Ragging the Popular Song Hits" that, in addition to the popular song hits of the time, included the following "silent movie music" based on themes by classical music composers (and even though the following compositions are not heavily syncopated and many were arranged by in-house arrangers, it would not be difficult for the serious student to "rag" these classical compositions):

v) Miscellaneous [toc] [top] Included in this section are various ragtime era compositions that "rag the classics" where I have not had time to expand on the composers or compositions in a section above dedicated to the particular composer:

3) Ragtime era composers who "classicized" ragtime [toc] [top] The ragtime compositions of the following ragtime composers likely fall into Schuller's categorization above of "classical" ragtime music where "classical yearnings" may be expressed in the overall mood or stance of a piece even where the piece cannot be tied to a particular piece of classical music. Simply put, whether you agree or not with Schuller's characterization, these are composers of "classic" ragtime whose works usually transcend the crassness of some Tin Pan Alley or honky-tonk ragtime music.

a) Eubie Blake [toc] [top] James Herbert "Eubie" Blake (7 February 1887 – 12 February 1983) was a legendary ragtime composer and performer, famous for a number of unique ragtime instrumentals and his partnership with Noble Sissle and their production of the Broadway Music Shuffle Along. In my separate essay on Ragtime in Canada, I discuss Eubie Blake's influence, along with John Arpin and other Canadians, of promoting the ragtime revival in Canada with Blake's many visits to Toronto in the 1969's and 1970's to perform. In Eubie Blake, author Al Rose describes Blake as having been "deeply affected by the music of Mozart, Chopin, Tchaikowsky, and George Gershwin" [Rose: 156] and describes the "classical" nature of Eubie's compositions in the following terms: It is as a composer of classics and semiclassics that Eubie has done sóme of his most exciting, though least known, work. "Dictys on Seventh Avenue," his "graduation piece" for his New York University degree, is in the Reginald Forsythe-David Rose mold but is nevertheless pure Eubie, as is his Gershwinesque "Capricious Harlem." Most surprising and most difficult to identify with Eubie are the two exotic etudes "Rain Drops" and "Butterfly." These delicate little tone poems are clearly in the genre of Debussy, with a hint of Richard Strauss. They are in no way imitative, though. It's just that these earlier composers established forms in which Eubie is supremely at ease. "Rain Drops" is built on a single note set ingeniously, like a diamond, in a ring of complex chords. It is slow in tempo, a "mood" piece, yet it is exciting. Excruciatingly restrained and suspenseful, it may ultimately go farthest in establishing Eubie's credentials in the ranks of formal classical composers. "Butterfly" has a more programmatic character. Eubie captures flutters and silences in a gossamer of taste and sensitivity. [Rose: 157-58]Some of Eubie Blake's more famous piano compositions include the following pieces:

b) Will Marion Cook [toc] [top] Will Marion Cook (January 27, 1869 – July 19, 1944) was an American composer, violinist, and choral director. His Wikipedia entry highlights Cook's fascinating life, including the following details: he was a student of Antonín Dvořák, he performed for King George V, he was the first black lawyer to practice in Washington, and was Dean of Howard University Law School. Cook is included in this essay for the following two of his compositions, which although clearly in the ragtime idiom, put Cook at an implicit intersection with classical musical given his classical music training:

c) Scott Joplin [toc] [top] In my separate essay in Scott Joplin, I set out commentary and links to all of the sheet music for his public domain ragtime music compositions. He is mentioned here despite not being known for ragging the classics as being a composer, like Nathaniel Dett, George Gershwin, and Artie Matthews, who had classical music aspirations, including his opera Treemonisha, believed to have been completed in 1910. More information on Treemonisha is available here; the Library of Congress also has an online essay on Treemonisha here. d) Joseph Lamb [toc] [top] In my separate essay on Joseph Lamb, I set out links to and discussion of all of his public domain piano sheet music, including those published by HH Sparks in Toronto when Lamb was a student in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, those published under not well-known pseudonyms with HH Sparks, and his "classic rags" published with Jospeh Stark in New York. Although Lamb was not known for "ragging the classics," he is included here for the classical music motifs found in one of his most famous Stark rags, Ragtime Nightingale (sheet music below), believed to have been written in response to James Scott's Ragtime Oriole (available here) even though it is likely that James Scott did not intend his work to be birdlike [Scotti (1977:90)], unlike the trio section of Lamb's Ragtime Nightingale which was intended in part to mimic the sounds of nightingale birds. In They All Played Ragtime, the authors quote Lamb describing the origins of Ragtime Nightingale and the influence of Ethelbert Nevin's Nightingale Song: I wrote heavy rags, the way I wanted whether it was hard to play or not. Chords might strike me first, or a melody, or a conjunction of chord and melody. I kept it working it over until I got something. With my Ragtime Nightingale, it was the name that struck me first. You may have noticed that in the beginning of the trio I use a little part of Ethelbert Nevin's Nightingale Song. I saw it in an Etude magazine of my sisters'. I usually got one complete strain finished and the others would follow, but the strains have to fit with each other.The opening arpeggiated chord from Ragtime Nightingale is said to have also been based on Chopin's Etude in C Minor, Opus 10, no 12 ("Revolutionary Etude").

e) Artie Matthews [toc] [top] Artie Matthews (15 November 1888 – 25 October 1958) was a ragtime composer most famous for his "Pastime" rags (below) and Weary Blues (1915). Matthews also arranged Baby Seals Blues (by Baby F. Seals) (1912) and Birmingham Blues (with Charles McCord) (1922), among other things. Like Nathaniel Dett, Artie Matthews focused on classical music after the ragtime era ended by establishing with his wife Anna in 1921 the Cosmopolitan School of Music, a music school for African Americans, where Matthews taught until his death. In Ragtime: An Encyclopedia, Discography, and Sheetography, David Jasen says this about Artie Matthews in describing the "Pastime" rags: The five "Pastimes" reveal his milieu in theatre work; they are bold and dramatic, extraordinarily pianistic, and reflect the vaudeville side of ragtime, but within the polished Classic rag format. From the perspective of early Classic ragtime, these works are innovations in the idiom [Jasen: 142-43].

The ragtime era, traditionally viewed as being from 1899 to 1919, was gradually eclipsed by the growth and popularity of jazz music, a phenomena that also saw classic music being "jazzed" in the same way that it had been "ragged" in the past. This section discusses the following jazz era composers and performers who "jazzed" the classics in one way or another along with those ragtime and jazz composers from the ragtime revival era to present who have ragged or jazzed the classics:

a) George Gershwin [toc] [top] George Gershwin (26 September 1898 – 11 July 1937) was a prolific composer whose short career spanned ragtime, jazz, Broadway musicals, classical music and Hollywood film scores. Some of Gershwin's more well-known compositions include Swanee (1919), Rhapsody in Blue (1924), Fascinating Rhythm (1924), Concerto in F (1925), An American in Paris (1928), I Got Rhythm (1930), and Porgy and Bess (1935). He has not yet been widely discussed on this website since my focus is on instrumental ragtime piano from the era of classical ragtime piano (circa 1899 to 1917). Gershwin is included here despite not having published music that ragged the classics because he, like Nathaniel Dett, Scott Joplin and Artie Matthews, gained experience composing traditional ragtime but "evolved" to compose or focus on classical music (and, in Gershwin's case, orchestrated jazz music) and otherwise is someone whose compositions would fall into Schuller's notion above that classical yearnings in ragtime era compositions may be expressed in the overall mood or stance of a piece. In That American Rag [Jason and Jones (2000): 289], the authors describe Gershwin's work as a teenager as a song-plugger for Joseph Remick in New York: For 3 years in the mid-teens Remick's star demonstrator was George Gershwin, who pounded out the firm's tunes in a piano cubicle for $15 a week. Gershwin was not able to place his own songs with his employer during his tenure, but in June 1917, three months after he left, Remick published his only rag, Rialto Ripples (co-composed with Will Donaldson).During that time, Gershwin is said to have recorded hundreds of piano rolls, sometimes under aliases such as Fred Murtha and Bert Wynn, including his Perfection #86738 piano roll (as Fred Murtha) of Artie Matthews' Pastime Rag No 3. For a video performance of Rialto Ripples by Jeffrey Biegel, click here. For commentary on Rialto Ripples, click here. Gershwin is also included here for the rag version he wrote as a teenager on Robert Schumman's "Traumerei" from Kinderszenen, Op 15, in the following composition, available now only as a recording:

For commentary on the foregoing composition, see:

b) Alec Templeton [toc] [top] As noted in his Wikipedia entry, Alec Templeton (4 July 1909/10 – 28 March 1963) was a Welsh composer, pianist and satirist. Blind from birth and gifted with absolute pitch, Templeton wrote and performed a number of novelty songs. Much of Templeton's output has been recorded on piano rolls even though not many of his piano compositions appear in print. For examples of some of Templeton's entertaining recordings that touch upon "jazzing the classics," see:

The following commercial recordings of Alec Templeton are likely difficult to source:

Since much of Fats Waller's music may be covered by copyright, depending on your jurisdiction, the sheet music to the foregoing piece, along with many of his other compositions, is available for purchase here (a different folio without the foregoing piece is also here). d) Modern examples of ragging and jazzing the classics [toc] [top] In this section, I briefly set out information on contemporary ragtime musicians and composers who have "ragged" or "jazzed" the classics or who otherwise fall within my broad definition as composers or performers of "classical" ragtime (set out below roughly by age of composer or performer):

His fingers waggle to and fro, with syncopated tremolo

Although the following composition by Darch is not an example of "ragging the classics" (but instead his tribute to Piper's Opera House in Virginia City, Nevada), it may still be of interest to some readers (and was purportedly arranged by Joseph Lamb):

Since Bolcom's compositions are still protected by copyright, you will not find them online. However, the following folio is highly recommended for purchase from your preferred bookseller:

The folio for Blue Gardenia contains the following tangos by Hal Isbitz and is available for purchase from the composer [hal "at" silcom.com]: At Midnight, Blue Gardenia, Caterina, Copacabana, Dolores, The Flirt, Margarita, La Mariposa, Meditation, Miranda, Morelia, and Pierre.

The foregoing folio also includes Jenks' "desecration" of a number of classical music compositions, as follows:

Glenn Jenks also composed a String Quartet in Ragtime (the sheet music for which I do not yet see as being easily available for purchase). For a performance of this piece by the Vanadium String Quartet, see:

a) William Levi Dawson [toc] [top] William Levi Dawson (September 26, 1899 – May 2, 1990) was an African-American composer, born at the start of the ragtime era, whose career and music focused on orchestral compositions and arrangements for choirs, including those based on African spirituals. In 1934, the Philadelphia Orchestra, led by conductor Leopold Stokowski, debuted Dawson's Negro Folk Symphony (audio recording available here), which, according to the Wikipedia entry for Dawson, he later revised in 1952 with added African rhythms inspired by the composer's trip to West Africa. Additional resources:

b) Claude Debussy [toc] [top] Claude Debussy (22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer known for such pieces as Clair de Lune (1890) ([view sheet music] [listen to Debussy playing his own composition] [listen to Jonny May's ragtime version]) and 2 Arabesques (1890) ([view sheet music] [listen to Debussy's version]). Like his contemporaries Erik Satie (below), Maurice Ravel (below), and Igor Stravinsky (below), Claude Debussy explored ragtime and jazz music in his own compositions, the most famous example of which is Golliwog's Cakewalk from his six-movement suite, Children's Corner:

The Wikipedia entry for the following cakewalk notes Debussy's allusions to banjo chords and drums heard from ministrel shows:

Debussy continued to explore ragtime themes in the following composition:

According to the Wikipedia entry for the following waltz, Debussy debuted it at the New Carlton Hotel in Paris, where it was transcribed for strings and performed by the popular 'gypsy' violinist, Léoni, for whom Debussy wrote it (and who was given the manuscript by the composer):

The following piece was apparently written about the American clown, Edward Lavine, whose costume was part soldier, part clown:

c) Nathaniel Dett [toc] [top] R

Nathaniel Dett, born in Canada, was a composer

who wrote in the ragtime idiom early in his career,

despite being known primarily for his compositions of

classical music and spirituals. His three earliest known compositions were in the ragtime mode, being After the Cake Walk, Cave of the Winds, and Inspiration Waltzes: In After the Cake Walk (1900), Dett has written what he described as a "March Cake Walk" in the key of G major with the Trio and final sections in the key of C major. It is an energetic, lightly syncopated and rhythmic piece in the ragtime march tradition:

In Cave of the Winds (1902), also in the keys of G and C major, Dett has written what is described by McBrier (Lerma and McBrier 1973:ix) as a vigourous march using simple traditional harmony. The title refers to the "Cave of the Winds" found at Niagara Falls, the city where Dett was living at the time he composed this piece:

In the typical fashion of a romantic, Dett describes the "inspiration" for Inspiration Waltzes (1903) in the introduction to this piece as follows: "I awoke one night at midnight and heard, as in a dream, the melodies of this Waltz played over and over, until I again fell asleep. Next morning I found it was still fresh in my memory. I created the Introduction and some other parts to give the whole completeness, but the main themes were truly 'Inspirations' or, to put it more poetically were truly 'dictated' by the Muse."

Although I have been unable to obtain a copy of the following piece, from its title, it is reasonable to assume the piece is more closely tied to the ragtime idiom than classical music.

With the publication of Magnolia: Suite for Piano, we can see Dett's evolution beyond stereotypical ragtime influences:

In I'll Never Turn Back No More, Dett has written a gospel choir dedicated to his two choirs, The Hampton Choral Union of the Hampton-Phoebus Community and The Institute Choir of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute:

In the introduction to In the Bottoms immediately below, Dett describes the piece as a suite of five numbers "giving pictures of moods or scenes peculiar to Negro life in the river bottoms of the Southern sections of North America."

One of those five suites from In the Bottoms is a moderately syncopated dance entitled Juba and is arguably the most well-known of the five suites and is included below as a "stand alone" composition:

Dett, whose mother was Canadian, was born in Drummondville, Ontario (later incorporated into Niagara Falls, Ontario) and showed promise on the piano as a young boy and was given piano lessons. During the time he composed the three ragtime-related pieces above, Dett was an organist at a church in Niagara Falls. He later studied at the Oliver Willis Halstead Conservatory in Lockport, New York from 1901 to 1903 and then at Oberlin College (Ohio) from 1903 to 1908, where he was the first African-American to earn a Bachelor of Music degree with a major in composition and the piano. He later obtained a Master of Music degree in 1938 from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. After the publication of his early more ragtime-influenced pieces listed above, and after attending music school, Dett's compositions took on a much more classical tone, incorporating Negro spirituals and other ethnic elements. Dett's music falls with the sphere of romanticism, with highly lyrical and thematic moods. In addition to composing, Dett spent most of his working life teaching at various music faculties in the United States and touring and performing his music (including tours to Canada and to Europe). His other major works include Enchantment: A Romantic Suite on an Original Program (1922), Cinnamon Grove: A Suite for the Piano (1928), Tropic Winter: Suite for the Piano (1938) and Eight Bible Vignettes (1941 ~ 1943). During the

latter part of his life, Dett struck up a friendship

with musician Percy Grainger (discussed below), composer of, among

other pieces, In

Dahomey: Cakewalk Smasher). The Sibley Music Library at the Eastman School of Music at the

University of Rochester has an extensive R. Nathaniel Dett collection. It remains unclear whether the ragtime music of Scott Joplin influenced Dett or whether Joplin himself knew of Dett, especially given Joplin's proclivity to be taken seriously as a composer. Much of the literature is silent on this point, with there being no mention of Dett in either They All Played Ragtime (Blesh and Janish 1966) and That American Rag (Jasen and Jones 2000). Edward Berlin does mention Dett in Ragtime: A Musical and Cultural History (Berlin 1980:107) in the context of musical rhythms found in musical sources of early ragtime. Given that Dett was driven in the early 1900's to write ragtime-related pieces, it is reasonable to assume that he knew of Scott Joplin during his career, given the general popularity of ragtime music that spread throughout the North East at that time. Dett himself, in moving towards more classical compositions, was perhaps trying to avoid stereotyped ragtime sounds. In a note to In the Bottoms, Dett refers to the common rhythmic figure found in ragtime music as being a "frequent occurrence in the music of the ante-bellum folk-dances" with "its marked individuality" causing "it to be much misused for purposes of caricature." Simpson (1993:11) describes Dett's "shame" when being exposed to Antonín Dvořák's incorporation of Negro and Indian musical heritages into his music when "the naive young Dett revealed embarrassment that musically his race was identified only with the current and frivolous ragtime style." Simpson later notes, however, that later on, "while a student at Oberlin College, Dett fortunately developed a broader, more cheerful perspective of the larger Negro idiom" but even as late as 1918 Simpson notes (1993:12) that Dett commented on the attitude of a majority of the black race in an interview carried by Musical America:

However, it is less certain whether Joplin knew of Dett and his music. The possibility exists that perhaps he did not, given the regional differences that "served as barriers to a shared culture" and that affirmed "the existence of diverse experiences within the African American community in the United States" at that time (Curtis 1994:188). Since Dett's classical compositions came towards the end of Joplin's life, and given the state of communications in those days, it is entirely possible that Joplin died, dreaming of his own classical ambitions with the publication of his opera Treemonisha without knowing of the classical publications of R. Nathaniel Dett. A more detailed analysis of Dett's life and his (classical) music is provided by Simpson (1993). Dett died of a heart attack on October 2, 1943, but his legacy lives on in Canada through The Nathaniel Dett Chorale, described on their website as "Canada's first professional choral group dedicated to Afrocentric music of all styles including classical, spiritual, gospel, jazz, folk and blues." For a good recording of Dett's music, see the following CD: Denver Oldham: R. Nathaniel Dett: Piano Works (1988).d) Louis Moreau Gottschalk [toc] [top] Louis Moreau Gottschalk (8 May 1829 – 18 December 1869) was a New Orleans composer and performer who spent most of his professional career outside of the United States but whose music was infused with African and Caribbean motifs and rhythms. In They All Played Ragtime, authors Blesh and Janis describe Gottschalk's work as an early precursor to ragtime with Gottschalk's incorporation of African and Caribbean drumbeats in La Bamboula – Danse des Nègres (below): It was in 1847, a half century before the first ragtime composition was published, that eighteen-year old Louis Moreau Gottschalk, son of an English cotton broker and a highborn French Creole lady, wrote the long, vastly difficult piano fantaisie La Bamboula – Danse des Nègres. A prodigy at fifteen, Gottschalk had already established himself in concert at the Salle Pleyel in Paris with huge public success and the praise of the great Chopin. La Bamboula is the composer's Opus 2; La Moree (Gottschalk was playing this "Ode to Death" at Rio de Janeiro when fatally stricken in 1869) is his Opus 60, but the earlier work with its strong Negroid inspiration is considered his masterpiece [Blesh and Janis: 82].The compositions by Gottschalk that reflect his melding of African and Caribbean melodies and rhythms and of the most likely interest to ragtime piano performers include but are not limited to the following pieces:

For commercial recordings of Gottschalk, consider the following:

e) Percy Grainger [toc] [top] Percy Grainger (8 July 1882 – 20 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. Although he is often noted for his arrangements of English folk songs, like the popular Country Gardens [view sheet music] [listen to a recording by the composer], he is included here for his showpiece composition, In Dahomey: A Cakewalk Smasher, based on tunes from In Dahomey by Will Marion Cook and a song by Arthur Pryor:

Another interesting composition by Grainger, albeit likely outside the scope of this essay, is his Handel in the Strand ("Room-Music Tit-Bits No 2"). Lewis Forman, in "Miscellaneous Works" in The Percy Grainger Companion [Forman: 137], notes that the piece was originally titled Clog Dance and explains why the name of the composition was changed: Handel in the Strand ("Room-Music Tit-Bits No 2") was originally entitled Clog Dance, but its dedicatee, the banker William Gair Rathbone, who had befriended Grainger, suggested the evocative title eventually used. He felt that the music "seemed to reflect both Handel and English Musical Comedy," the home of the latter being The Strand in London's West End. Grainger tells us that in bars 1 to 16, and their repetition at bars 47 to 60, he made use of matter from some variations he wrote on Handel's "Harmonious Blacksmith" tune. [Forman: 138]

The foregoing does not do justice to Grainger's life or his work and glosses over what appears to have been his sadomasochism [note: the link is safe] and his antisemetic views [see, for example, Sarah Kirby, "Cosmopolitanism and Race in Percy Grainger’s American 'Delius Campaign'" (Fall 2017) Current Musicology 25]. Given more time, Grainger is one composer whose works and life I would like to research further, including his gathering of English folks songs on wax cylinders and his free music machines. For recordings of Grainger's work, see:

f) Arthur Honegger [toc] [top] Arthur Honegger (10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a European composer, born in France to Swiss parents, who lived in Paris. The following of his compositions are regarded by many as being infuenced by African-American ragtime: In Pacific 231, for example, Honegger is thought to have created the sound of a steam locomotive gaining power despite Honegger's notion that he wrote it as an exercise in building momentum while the tempo of the piece slows, a noted in the Wikipedia article ahout this composition:

Another Honegger composition influenced by ragtime is the following piece:

The following compositions consists of three pieces: Prélude, Hommage à Ravel, and Danse:

g) Charles Ives [toc] [top] Charles Ives (20 October 1874 – 18 May 1954) was an American composer born in Danbury, Connecticut and later affiliated with Yale University. His early compositions are noted for their incorporation of ragtime motifes, including the following pieces:

h) Darius Milhaud [toc] [top] Darius Milhaud (4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer and conductor who incorporated ragtime and jazz into some of his compositions, including the following pieces:

In his article "Jazz Band and Negro Music" (October 1924) Living Age 169 at 171, Milhaud puts American orchestrated jazz music as a sui generis on par with classical music and was critical of the practice of "ragging the classics": It was a mistake to adapt pieces of music already famous — ranging from Tosca's prayer to 'Peer Gynt' or Grechaninov's Berceuse — making use of their melodic In jazz the North Americans have really found expression in an art form that suits them thoroughly, and their great jazz bands achieve a perfection that places them next our most famous symphony orchestras like that of the Conservatoire or our modern orchestras of wind instruments and our quartettes — the Capet Quartette, for instance, which is our very best.For further reading on this composer, see:

i) Ernesto Nazareth [toc] [top] Ernesto Nazareth (20 March 1863 – 1 February 1934) was a Brazilian composer and pianist known for his extensive composition of Brazilian tangos or "choro" music. Similarities can likely be drawn between Nazareth and Scott Joplin: they were relative contemporaries, a sense of melancholy floats throughout their music, and their lives ended in similar but separate, relatively tragic circumstances (hospitalization and eventual death due to suspected complications from syphillis). Set out below is a list of some of my favourite tangos and waltzes by Nazareth and of most likely interest to ragtime piano performers (click on the title for the sheet music):

There are a number of online recordings of performances of Nazareth's music. For a good commercial recording that includes a number of Nazareth's tangos, see Joshua Rifkin, Rags and Tangos (Decca 2016). j) Ethelbert Nevin [toc] [top]

Nevin is included here for the following reasons:

k) Maurice Ravel [toc] [top] Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor famous for such compositions as Gaspard de la nuit (1908), Daphnis et Chloé (1912), and Boléro (1928). Ravel is included here primarily for his incorporation of ragtime, jazz and blues into some of his compositions written during the ragtime era, including the following pieces:

l) Erik Satie [toc] [top] Erik Satie (17 May 1866 – 1 July 1925) was a French avant-garde composer and pianist whose well known compositions include the following pieces:

m) John Philip Sousa [toc] [top] John Philip Sousa (6 November 1854 – 6 March 1932) was an American composer and band conductor known for his military marches that preceded and continued through the ragtime era. In The Music Trade Review (3 October 1903) 37:14, Sousa's enthusiasm for ragtime is quoted in the following terms: Ragtime is an established feature of American music; it will never die, say more than Faust and the great opera will die. Of course, I don't mean to compare them musically, but ragtime has become as firmly established as the others, and can no longer be classed as a craze in music. Nearly everybody likes ragtime. King Edward VII liked it so well that he asked us to play more of it, and we gave him "Smokey Mokes" and "Georgia Camp Meeting." Emperor William and the Czar were also converted to ragtime. It is just as popular everywhere as it ever was, and I see no reason why it should not remain in favor as long as music is played.George Cobb (above) in his "Just Between You and Me" column from (October 1919) 10:3 Melody 12 described attending a Sousa concert in 1919: On Sunday afternoon, September 21st, at Symphony Hall in Boston I had the pleasure of hearing Sousa's Band play to a much crowded house ... It is almost superfluous to talk about the playing of the Sousa Band, but ... I must say a word about this artistic bunch. I have heard the Sousa aggregation many times before, but I have never heard them play as they did at this concert and that is saying a great deal — time, tempos, technic, tunes and TONE (I can't think of any more "T"s) — all being combined to make the perfect whole in band ensemble artistry, and winning round after round of appreciative applause from the audience.He then describes meeting Sousa backstage: [Joseph Green from Sousa's Band] asked me if I would like to meet John Philip Sousa himself. I admitted that I would — amd I did, which was a most unexpected pleasure. After an exceedingly friendly hand-shake. I told the great band leader I had wanted to grip the Sousa baton-bunch-of-fives ever since I was knee-high to a cootie. He smiled out loud, and said some very compimentary things about "Peter Gink"....The sheet music (and in some situations, the orchestral score) of some of Sousa's most famous compositions, and those of most likely interest to ragtime performers, are included below (click on the title for the sheet music):

For additional resources on John Philip Sousa, see:

n) William Grant Still [toc] [top] William Grant Still (11 May 1895 – 3 December 1978) was an African-American composer of symphonies, ballets, operas, choral works and other works. He is listed here primarly for his Afro-American Symphony (1930), described in the Wikipedia article for this composition as "a symphonic piece for full orchestra, including celeste, harp, and tenor banjo" that "combines a fairly traditional symphonic form with blues progressions and rhythms that were characteristic of popular African-American music at the time" and "expressed Still's integration of black culture into the classical form." Click here for a performance of the Afro-American Symphony by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Given more time, I would hope to expand upon this entry in the future. Otherwise, there are a number of books providing more information on this composer:

o) Igor Stravinsky [toc] [top] Igor Stravinsky (17 June 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor known for a diverse style of compositions. Early in his career, he became known for his works for the ballet, including The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911), and The Rite of Spring (1913). The following Stravinsky compositions are said to contain ragtime allusions:

For more information on Stravinsky, see:

Where free

online recordings are available for any composition

listed on this page, links have been included above

for the particular piece being discussed. In this

section, I instead set out information on recordings

of "ragging" or "jazzing" the classics in the

following categories:

a) CDs and other

commercial recordings Set out below

are CDs that contain tracks of songs "ragging" or

"jazzing" the classics:

Author Al Rose quotes Eubie Blake in describing John Arpin in the following terms: "I call him the Chopin of ragtime. I sat around all night waiting to hear him make a mistake. He never made one. He plays so beautiful it makes me cry. And he really did a lot for ragtime in Canada": [Rose: 151]. I highly recommend this CD.

b) Free

online videos or audio files of performances Set out below

are some of my favourite online performances of

"ragging" or "jazzing" the classics:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This site created by Ted Tjaden. Page last updated: January 2026.

|